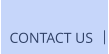

I, Sarah Steinway

— A Novel —

arah Steinway survives a catastrophic

flood by moving into her treehouse

located on the northern shoreline of the San

Francisco Bay. Sarah, aged seventy-five,

observes from her perch a rise in sea level that

engulfs the entire landscape for as far as she

can see. With snark and pluck, she survives in

her treehouse for five years.

She records the flood, narrates her survival,

and leavens her story with gusts of biting

humor. Somewhat sheepishly as a secular

Jew, Sarah turns for comfort to Torah. Instead

of finding solace, she engages in tart

argumentation with God, raising her fists,

shouting the eternal Jewish question: ‘Why

me?’

“The whole book could be considered a postdiluvian midrash.”

—Rabbi Deborah J. Brin, Mishkan of the Heart

Winner 2018 New Mexico-Arizona Book Awards

Finalist National Jewish Book Awards - Debut Novel

“An utterly original imagining of a

post-apocalyptic world, lightly using the tropes of dystopian and disaster fiction while

depending on ingenuity and emotional depth to carry the story.”

—Quarter-Finalist Publishers Weekly

— BookLife Prize

“Carter’s captivating, vividly imagined tale unfolds with terrifying beauty as protagonist

Sarah Steinway grapples with survival in a future climate change disaster. Carter’s novel

is an utterly original imagining of a post-apocalyptic world, lightly using the tropes of

dystopian and disaster fiction while depending on ingenuity and emotional depth to carry

the story. Savvy cultural references bring an immediacy and freshness to the text.”

— Publishers Weekly BookLife Prize

Critic’s Report

Imaginative technique of Midrash (homiletic expansion on the primary text) to make her

points. “Apocalyptic novels may not be your cup of tea (or glass of Chateau Lafitte in the

case of this book’s eponymous character), but I, Sarah Steinway is yet another example of

excellent, witty, and thought-provoking writing by Mary E. Carter. Water featured

prominently in her previous work, A Non-Swimmer Considers Her Mikvah, and Carter

returns to water, this time of the flood variety, in her latest novel. Our heroine is quite a

character and knows just how to use the imaginative technique of Midrash (homiletic

expansion on the primary text) to make her points from a Jewish perspective. And while

Sarah spends the bulk of her time alone in a treehouse, we are eventually introduced to a

pair of “out-of-this-world” rabbis. Each chapter of this book cites a passage from the classic

ethical Jewish treatise, Pirke Avot, so I suggest you drink in Carter’s words thirstily (Pirke

Avot 1:4) and put on your galoshes for a wild ride with Sarah Steinway.”

—Rabbi Jack Shlachter,

Judaism for Your Nuclear Family,

physicsrabbi@gmail.com – www.physicsrabbi.com

“Despite being self-declaredly secular, the very vernacular of Sarah’s impassioned

arguments with God place her squarely in a long line of Jews shaking their fists at the

disputed heavens.”

—Faber Academy Reader

“Sarah Steinway is a stubborn, angry, resourceful, funny, inquisitive and independent

woman. Those traits help her survive in Mary E. Carter’s thought-provoking debut novel . .

.

Sarah is the joyful, complex hero-figure in Carter’s post-apocalyptic novel set in the not-

so-distant future.”

— David Steinberg, Albuquerque Journal

“The character of Sarah Steinway is indeed a human being; feisty, flawed and utterly

engaging. Highly recommended.”

— Sheryl Stahl, Director,

Frances-Henry Library, HUC-JIR, Los Angeles

$15.50

ISBN 978-0-692-98524-3

Paperback 212 pages

Published by

Tovah Miriam Gershom

Available from Ingram

or from Amazon.com or by Consignment

Copyright ©2024 by Mary E. Carter

I, Sarah Steinway

— A Novel —

Sarah Steinway survives a catastrophic flood by

moving into her treehouse located on the

northern shoreline of the San Francisco Bay.

Sarah, aged seventy-five, observes from her perch

a rise in sea level that engulfs the entire landscape

for as far as she can see. With snark and pluck,

she survives in her treehouse for five years.

She records the flood, narrates her survival, and

leavens her story with gusts of biting humor.

Somewhat sheepishly as a secular Jew, Sarah

turns for comfort to Torah. Instead of finding

solace, she engages in tart argumentation with

God, raising her fists, shouting the eternal Jewish

question: ‘Why me?’

“The whole book could be considered

a postdiluvian midrash.”

—Rabbi Deborah J. Brin, Mishkan of the Heart

Winner 2018 New Mexico-

Arizona Book Awards

Finalist National Jewish Book

Awards - Debut Novel

“An utterly original imagining of a

post-apocalyptic world, lightly using the tropes

of dystopian and disaster fiction while

depending on ingenuity and emotional depth to

carry the story.”

—Quarter-Finalist Publishers Weekly

— BookLife Prize

“Carter’s captivating, vividly imagined tale

unfolds with terrifying beauty as protagonist

Sarah Steinway grapples with survival in a

future climate change disaster. Carter’s novel is

an utterly original imagining of a post-

apocalyptic world, lightly using the tropes of

dystopian and disaster fiction while depending

on ingenuity and emotional depth to carry the

story. Savvy cultural references bring an

immediacy and freshness to the text.”

— Publishers Weekly BookLife Prize

Critic’s Report

Imaginative technique of Midrash (homiletic

expansion on the primary text) to make her

points. “Apocalyptic novels may not be your cup

of tea (or glass of Chateau Lafitte in the case of

this book’s eponymous character), but I, Sarah

Steinway is yet another example of excellent,

witty, and thought-provoking writing by Mary E.

Carter. Water featured prominently in her

previous work, A Non-Swimmer Considers Her

Mikvah, and Carter returns to water, this time of

the flood variety, in her latest novel. Our heroine

is quite a character and knows just how to use the

imaginative technique of Midrash (homiletic

expansion on the primary text) to make her points

from a Jewish perspective. And while Sarah

spends the bulk of her time alone in a treehouse,

we are eventually introduced to a pair of “out-of-

this-world” rabbis. Each chapter of this book cites

a passage from the classic ethical Jewish treatise,

Pirke Avot, so I suggest you drink in Carter’s

words thirstily (Pirke Avot 1:4) and put on your

galoshes for a wild ride with Sarah Steinway.”

—Rabbi Jack Shlachter,

Judaism for Your Nuclear Family,

physicsrabbi@gmail.com –

www.physicsrabbi.com

“Despite being self-declaredly secular, the very

vernacular of Sarah’s impassioned arguments

with God place her squarely in a long line of

Jews shaking their fists at the disputed heavens.”

—Faber Academy Reader

“Sarah Steinway is a stubborn, angry,

resourceful, funny, inquisitive and independent

woman. Those traits help her survive in Mary E.

Carter’s thought-provoking debut novel . . .

Sarah is the joyful, complex hero-figure in

Carter’s post-apocalyptic novel set in the not-so-

distant future.”

— David Steinberg, Albuquerque Journal

“The character of Sarah Steinway is indeed a

human being; feisty, flawed and utterly

engaging. Highly recommended.”

— Sheryl Stahl, Director,

Frances-Henry Library, HUC-JIR, Los Angeles

$15.50

ISBN 978-0-692-98524-3

Paperback 212 pages

Published by

Tovah Miriam Gershom

Available from Ingram

or from Amazon.com or by Consignment

Copyright ©Mary E. Carter

Mary E. Carter ~ Author